American aviator, military officer, author, inventor, and activist Charles Augustus Lindbergh On May 20–21, 1927, at the age of 25, he made history by flying the first nonstop flight from New York City to Paris. Lindbergh flew solo in a purpose-built, single-engine Ryan monoplane, the Spirit of St. Louis, for the 33+12-hour, 3,600-statute-mile (5,800-kilometer) flight. Even though the first nonstop transatlantic flight had been completed eight years before, this was the first solo transatlantic flight, the first transatlantic flight between two major city hubs. It was one of the most important flights in aviation history, ushering in a new era of global transportation. On the other hand, in World War II history, there are a lot of famous pilots.

The Early Life of Lindbergh

Lindbergh was born on February 4, 1902, in Detroit, Michigan, and spent most of his childhood in Little Falls, Minnesota, and Washington, D.C. He was the only child of Charles August Lindbergh (birth name Carl Mansson; 1859–1924) and Evangeline Lodge Land Lindbergh (1876–1954) of Detroit. Lillian, Edith, and Eva were Lindbergh’s paternal half-sisters. When Lindbergh was seven years old, the couple divorced in 1909. His father is a U.S. Marine. Although his congressional term ended one month before the House of Representatives voted to declare war on Germany, Congressman (R-MN-6) was one of the few congressmen to oppose the United States’ entry into World War I.

Lindbergh’s mother taught chemistry at Detroit’s Cass Technical High School and then at Little Falls High School, where her son graduated on June 5, 1918. During his childhood and adolescence, Lindbergh attended over a dozen other schools from Washington, D.C., to California, including the Force School and Sidwell Friends School in Washington with his father, and Redondo Union High School in Redondo Beach, California, with his mother. Lindbergh enrolled in the University of Wisconsin–College Madison’s of Engineering in late 1920, but dropped out in the middle of his sophomore year and moved to Lincoln, Nebraska, in March 1922 to begin flight training.

Lindbergh enlisted in the United States Army

Lindbergh enlisted in the US Army in 1924 to be trained as an Army Air Service Reserve pilot. He was the best pilot in his class when he graduated from the Army’s flight-training school at Brooks and Kelly fields near San Antonio in 1925. After completing his Army training, Lindbergh was hired by the Robertson Aircraft Corporation of St. Louis to fly mail between St. Louis and Chicago. He established himself as a cautious and capable pilot.

The Orteig Prize

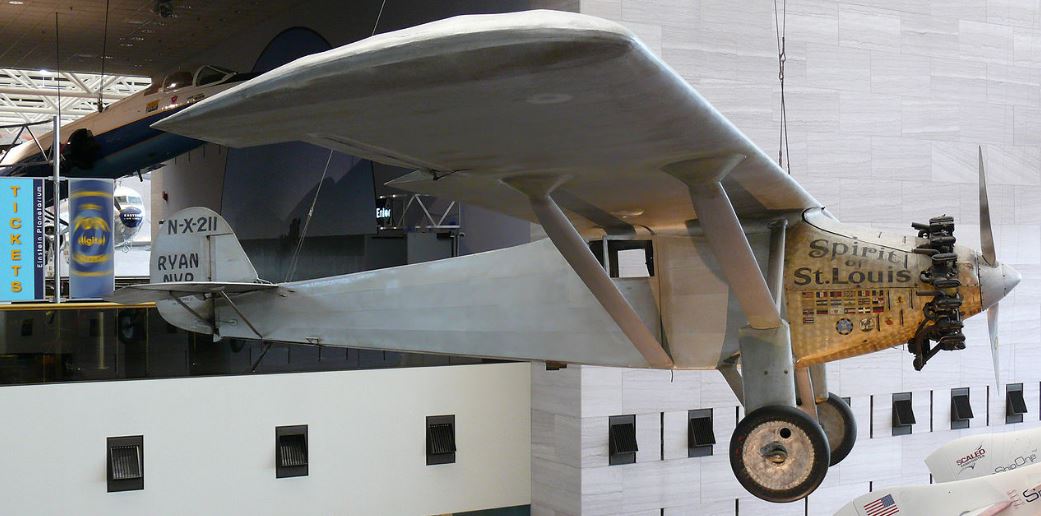

In 1919, Raymond Orteig, a hotel owner in New York City, offered $25,000 to the first aviator to fly nonstop from New York to Paris. While competing for the Orteig prize, several pilots were killed or injured. It had still not been won by 1927. Lindbergh believed that if he had the right plane, he could win. He persuaded nine businessmen in St. Louis to help him finance the plane. Lindbergh chose San Diego’s Ryan Aeronautical Company to build a special plane that he helped design. The plane was given the name Spirit of St. Louis by him. Lindbergh put the plane to the test by flying from San Diego to New York City on May 10–11, 1927, with an overnight stop in St. Louis. The flight took a transcontinental record of 20 hours and 21 minutes.

The Flight of Lindbergh

At 7:52 a.m. on May 20, Lindbergh took off from Roosevelt Field, near New York City, in the Spirit of St. Louis. On May 21, at 10:21 p.m., he landed at Le Bourget Field, near Paris. Time in Paris (5:21 P.M. New York time). Hundreds of thousands of people had gathered to greet him. In 33 1/2 hours, he had flown more than 3,600 miles (5,790 kilometers).

Lindbergh’s daring flight inspired people all over the world. Awards, celebrations, and parades were held in his honor. The Congressional Medal of Honor and the Distinguished Flying Cross were awarded to Lindbergh by President Calvin Coolidge.

Lindbergh published We, a book about his transatlantic flight, after the flight in 1927. Lindbergh and his plane were mentioned in the title. Lindbergh flew across the United States on behalf of the Daniel Guggenheim Fund for the Promotion of Aeronautics to promote air awareness. Lindbergh learned about Clark University physics professor Robert H. Goddard’s pioneer rocket research. Lindbergh persuaded the Guggenheim family to fund Goddard’s research, which eventually led to the development of missiles, satellites, and space travel. Lindbergh also worked as a technical adviser for several airlines. To know something from the past, there are a lot of aircraft or famous warplanes in history. It brought pride to the nation as it fought during World War.

The Guggenheim Tour

Before Charles Lindbergh flew to Paris, Harry Guggenheim, a multimillionaire from the North Shore and an aviation enthusiast, paid him a visit at Curtiss Field. “Look me up when you get back from your flight,” Guggenheim said, later admitting he didn’t think Lindbergh would survive the journey. When Lindbergh returned, he remembered and called. It was the start of a friendship that would have a significant impact on aviation development in the United States. The two decided that Lindbergh would go on a three-month tour of the United States, which would be funded by a fund Harry and his father, Daniel, had established earlier to promote aviation research. Lindbergh was given a three-month nationwide tour by the Daniel Guggenheim Fund. He visited 49 states, and 92 cities, gave 147 speeches, and rode 1,290 miles in parades while flying the “Spirit of St. Louis.” “As he flew around the country, Lindbergh was seen by literally millions of people,” said Richard P. Hallion, an Air Force historian and author of a book about the Guggenheims. As a result, “airmail usage exploded overnight,” and the public began to see airplanes as a viable mode of transportation. In addition, while writing “We,” his best-selling 1927 account of his trip, Lindbergh spent a month at Guggenheim’s Sands Point mansion, Falaise.

The Spirit of St. Louis

The aircraft was named “Spirit of St. Louis” in honor of Lindbergh’s supporters in St. Louis, Missouri, who paid for it. “NYP” stands for “New York-Paris,” the flight’s destination.

The Spirit of St. Louis is a fantastic aircraft. It’s as if it were a living creature, gliding along smoothly and happily, as if a successful flight meant as much to it as it did to me, as if we shared our experiences, each feeling beauty, life, and death as keenly as the other, each relying on the other’s loyalty. According to Charles Lindbergh in 1927, “We made this flight across the ocean, not I or it.”